Let me tell you about your infinite sons

Person A was walking her dogs along a building-lined street when she passed another person.

“The way you’re standing,” said A, “With your foot on the step and your elbow on the bannister, it’s obvious you’d like to speak.”

“Quite right,” said B. “I do have something in mind. Have you heard about my infinite sons? They are the source of my pride, and will inherit this world upon my passing.”

“Your infinite sons? I scarcely believe it.”

It was unbelievable. Ordinarily, such words would repel A away from this repugnant person. However, A’s three dogs had begun to pee in a small dry patch next to the sidewalk. A planted her marble walking stick firmly on the ground and leaned forward.

“How do you mean, your infinite sons?”

At once, B’s face became lit from within, engine whirring, and his hands carried about on a sudden wind.

“They are boundless, my sons.” His hands flapped endlessly. “They are as many as clouds, and they and their progeny will cover the earth like rain.”

A looked worryingly up at the overcast and now darkening sky. The doors lining the street rattled from currents that moved through the buildings.

“I hope not soon,” said A. Then, more firmly: “Sons cannot be rain.”

Unnoticed by the interlocutors, A’s first dog, peeing in the dirt, had drawn a lucid shape. Unsurprising, as the long leashes preferred by A allowed her dogs ample artistic leisure. The shape was nearly like a circle, and it looked like this:

“Incorrect,” said B. “My sons are rain. They are massy drops, permeating relentlessly.”

A shuddered visibly. Her stick slid on the sidewalk, belying the foundation. She couldn’t let this go on. She had to think of something.

“Your sons may be rain. But the earth is round.” She paused to think. “And if the earth is round, then your sons will surely roll off it. If not that,” she said, gaining steam, ”Then they will pool in low-lying areas, succumbing to agricultural runoff.”

“It’s a bad time to be water,” she added.

“Are you insane?” asked B. “What you say makes no sense. The ground under our feet is flat. My sons will not pool; they will sprawl equitably, spreading over the plane like water over a table. Their shoulders will touch end-to-end across this flatness, and comfortably so.”

A stood silently, mentally urging her dogs to wet the unhappy man. It was not her choice to make. The clouds started to close in.

B took advantage of the pause. “Moreover, my sons are like the light.”

A nearly screamed.

“No! They are not anything!” she yelped, helplessly. As she said this, however, small yellow rays began to pierce through the sky. It was something. She felt her stomach digest and sugar return to her blood. The doors along the street ceased to rattle.

It was more than something, she thought. With the light, something had occurred to her: an idea, fully formed, possibly irrefutable.

B continued: “My sons will shine bravely, peering into the night, torchlike.”

“Torchlike,” A repeated, stunned. “No, this cannot go on.”

B began to speak again, but A interrupted.

“This will not go on, because I agree with you,” A said. A surprising turn.

“You agree with me?” asked B. He paused for a moment to allow a smile to crawl from inside his mouth and thinly encircle his head.

“Yes, I agree. Without reservation,” A confirmed.

A’s second dog had begun to draft thin lines of urine over the shape the first dog had made. The figure was growing more complex. It now looked like this:

“This is good news! Now, I and my inf—”

“Stop talking,” said A. “Listen, now. Allow me to explain. Listen and allow me to find you your sons. Allow me to bring your sons finally and infinitely into being.” If only to dispel them forever, thought A.

B stood at attention, impressed.

“As you say, the earth is flat. Correct?” She was reviewing his notes.

“Yes. My sons, like divine wat—”

“Stop. And, as you say, your sons are also light. Yes?”

“That’s right.”

“Then look at this drawing in the dirt.”

B looked at the drawing in the dirt.

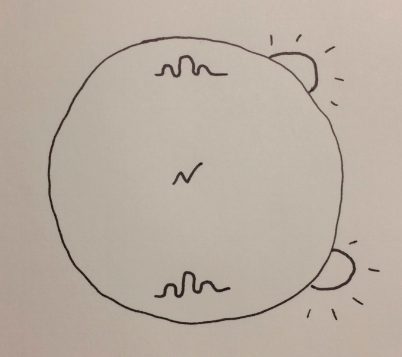

A used her walking stick to add marks to the image, which, then, looked like this:

“This is your flat earth. Those two rippled marks are shining cities, perched across the world from one another. Can you picture it?” The figure was conceptual, more or less. “The direction North, on a flat earth, is at the center of the disk. Do you see?”

“I follow. North. Two cities. Flat disk. And those two orbs at the right?”

“Those orbs you may recognize as two of your sons. On this flat earth, it is dawn. Or sunrise. One son rises above the horizon, East of one city, while another son sets, due West of the other. On the clock, these cities are twelve hours apart.”

A continued: “There must be two sons on this flat earth. Do you see why? One son cannot appear in two places, both rising and sinking, due East of one city and due West of another. Two sons. It must be so.”

B, nervously, “I follow. I see my sons.”

A’s third dog then approached the image and released a number of well-placed, ovular-shaped spurts. Walking stick in hand, A drew lines corresponding:

More sons and cities, it seemed.

“Now,” said A, “I present to you your infinite sons.” She bowed elaborately.

The street doors each opened to a bare crack, and one could hear faint chanting: “Find those sons. Find those sons…”

Find those sons.

It was clear to A that, to B, her meaning was unclear.” She tried to help: “Here are your sons in their entirety.”

“How?” pleaded B, horrified.

“Here’s the deal,” A said. “As I mentioned, your sons can’t be in two places at once. Now, every hour, there is a new sunrise and a new sunset. Twelve in total — for for twelve hours of sunlight. Right? Twelve sons. There are fewer than that, here, on the drawing. An aesthetic choice of my dog’s.”

“Still,” A continued. “There are twelve hours, but these also must be divided, for every possible moment of sunlight on the flat earth. Why? If, during the morning, you drive just five minutes West, the sun will rise later, there, than where you were before. For every possible moment, every inch: a sunrise, a noon, and a sunset, all orbiting the earth in continuous motion. Each of your infinite sons supplies an infinitely divisible but infinitely repeatable sliver of light. They illume the disk perfectly, a borderless strobe, and not one atom is spared their consuming gaze.”

B stood, for a moment, in silent terror. Through all cracked doors, a cheer — distant, rising, near. We were feeling a bit like cheering, too.

“This is overwhelming,” said B. He was feeling it. “This is too many sons, too much light. Too much — there cannot be so many sons.”

“There must be so many,” said A, who sealed the phrase with a hard rap from her walking stick. A current tore through B at the sound, revealing his eyes to be a translucent, blemishless white — there was no center.

“In a world as you have imagined it, your inheritance is divinely ordained,” said A. “Your infinite sons must inherit the earth — daily, continuously. That logic, that degree of truth, is absolute.”

B had begun to weep for reasons unseeable to him. The information A delivered appeared to be an assurance, but, mysteriously, offered nothing.

“The world, as you have imagined it, does not exist,” proclaimed A. The doors along the street flew open with sonorous wind.

“It is a fiction,” A continued. “I have performed your labor by revealing this fiction to you. However, your two eyes, peering scared from your skull, are sufficient instruments for revealing that the world is not as it exists only in your mind. There are no infinite sons above us. The earth is not flat. It is round. It curves. As of this moment, that world — your sons — are lost to you.”

All at the same time, A and her three dogs began to move along down the sidewalk.